Thursday, April 28, 2011

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

10 Things You Need to Know About the Deficit

- About half the deficit is because of the recession and Bush tax cuts. High unemployment means fewer people paying taxes, and the tax cuts mean they pay less when they do have jobs. We can argue whether that's fair or not, but the numbers are what they are.

(Income tax cuts do not increase net revenues except in extreme cases where, say, marginal rates are something on the order of 80-90 percent. Our top bracket is at 35 percent.)

The chart at right from CBPP breaks down the rest. Our wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are significant contributors, and the past couple years the stimulus factored in too. However, most economists, including conservative ones, agree that the stimulus saved a whole lot of jobs, which made a potentially disastrous situation just really bad.

- Taxes are at their lowest effective rates since 1950. We can disagree about what percentage of deficit reduction should come from tax increases rather than spending cuts, but we paid on average the lowest rates since 1950, and the big tax-cut package signed last December should decrease them further. Via Felix Salmon's blog:

- There has not been a massive spending binge under President Obama. Aside from the stimulus, Obama has ordered pay freezes and cuts to numerous programs. Refer back to point #1.

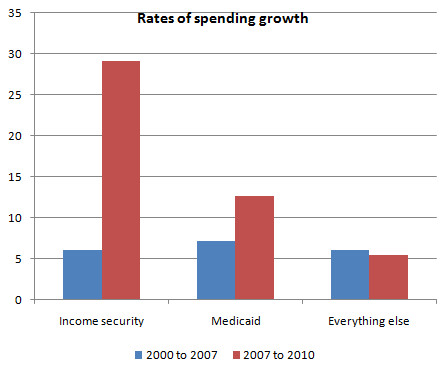

There has been a big rise in spending in one major area, though: safety net programs. This is spending that automatically kicks in during a recession, to pay for things like unemployment insurance, food stamps and Medicaid. Here's a good graph from Paul Krugman mapping it out (full article here). Note that spending on the kinds of things that don't rise automatically has gone up at a slower rate than under President Bush.

- The U.S. is responsible for almost half of the world's entire defense budget. Yes, we spend as much as almost every other country combined, and most of the next-biggest budgets belong to our allies. All this is the case despite there being little dispute that there is massive waste at the Pentagon, and there doesn't seem to be a coherent argument about why the budget level we have now is the right one, and why. Via Matt Yglesias:

You can also see a breakdown by country here.

- The few things everybody wants to cut are a tiny fraction of the budget. Americans are in favor of massive spending cuts in the abstract, just not in specifics. The popular impression seems to be that if only we didn't give money to foreign countries, NPR and lazy poor people, our problems would be solved. The reality is not close.

When you take out Medicare, Social Security, defense and interest payments on the debt, you're left with only about 15 percent of the budget. This includes a wide variety of categories: veterans benefits, agriculture programs, energy, education, transportation, social services, housing, the justice system, scientific research, environmental protection...the vast majority of the programs this chunk of the budget supports are some of the most popular things government does.

You can see a nice pie chart here.

- Our long-term entitlement problems are mostly because Boomers are retiring. The Boomer generation is the rabbit that's just been swallowed by the snake. All those workers are still pumping tax money into Social Security and Medicare, but as more reach retirement age, a smaller group of younger workers will be supporting their benefits. As the Economist reports, over the next 20 years, the share of the U.S. voting-age population over age 65 is expected to jump from 17 to 26 percent.

- Earmarks are not the problem. Earmarks accounted last year for less than 1 percent of the federal budget. It's not just that they're small potatoes, though. Earmarks don't actually even increase federal spending. They take the existing budget and rope off a certain portion for projects that Members of Congress think are the most important for their districts.

Whether they are wasteful or not is a separate argument...some clearly are, but not nearly as many as you think. The point here is that they were not the cause of the deficit crisis.

- It's about health care costs, not Medicare costs. This is a really important distinction. When we talk about entitlement reform, we look at how much Medicare is expected to cost us in the future and it's not pretty. But, it's not because Medicare costs so much, because in fact Medicare costs a lot less than private insurance for the same coverage. It's because health care costs so much.

Paul Ryan's budget proposes to solve the deficit in large part by privatizing Medicare by giving people vouchers to purchase coverage on the open market. This does nothing to stop the cost of health care from rising, though. It just puts the responsibility for keeping up with costs into each individual's hands, and gets rid of the central premise of Medicare: insurance. The plan would shrink government spending, but would increase overall spending by a great deal more than it cuts. This is hiding the problem and making it worse.

In contrast, the Affordable Care Act ("Obamacare") is projected by the Congressional Budget Office to cut the deficit by $143 billion over 10 years, making would make it the most effective deficit reduction legislation since the 1993 Budget Act. It should be noted that those projections assume no cost savings from a number of the pilot programs in the ACA, so there is plenty of potential upside to those figures.

Here's a nice chart Ezra Klein has used a few times before, but bears reposting. The left-hand axis shows spending as a percentage of GDP. It's about health care.

- The federal budget isn't like a household budget. It's tempting and understandable to make the argument that during an economic downturn, households have to tighten their belts, so the government should too. It's just common sense.

- Not raising the debt ceiling would be catastrophic. Follow me here: The argument against raising the debt ceiling, besides what is implicit in #8, is that our deficit spending will cause a crisis of confidence in the American economy. In the long run, this is probably true. However, nothing could undermine confidence in our economy faster than not our political system not being able to solve what should be a simple and obvious problem.

Short version: The rest of the world considers U.S. bonds to be the safest place to park money, making it extremely cheap for us to borrow. That, and the U.S. dollar's position as the world's default currency, could disappear overnight.

Ezra Klein says it best, as he often does:

To understand the danger posed by the debt ceiling, it helps to understand the financial crisis. A lot of banks and investors held assets based on mortgages they thought were safe. They weren’t. That meant that no one knew how much money they really had, or how much money anyone else really had. So the market did what woodland creatures do when they get confused and scared: It froze. And so, too, did the economy. As the unemployment rate shows, we’re still not completely thawed out.

If Congress fails to lift the debt ceiling beyond its current limit of $14.29 trillion — or even waits too long — the chain of events will be similar, but the asset under question will be America itself, not some newfangled Frankenstein bond made out of mortgages from the Reno suburbs. Which would mean the aftermath would be much, much worse.

“The cornerstone of the global financial system is that the United States will make good on its debt payments,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics. “If we don’t, we’ve just knocked out the cornerstone, and the system will collapse into turmoil.”

We are playing with fire right now, and if we aren't careful, we're in for a financial nightmare.

And it's exactly wrong. One of the major roles of the federal government is to be anti-cyclical. That is, a recession is the time when people are most in need of government programs to let the unemployed keep feeding their families and off the streets. The federal government should run deficits during recessions, and probably surpluses during good times. (Incidentally, this is why a cap on spending as a percentage of GDP is such a terrible idea.)

The problem with the current recession isn't that there isn't enough money available for people to go out and start businesses. It's that there isn't enough demand for the things businesses make and the services they provide. Businesses in many sectors have been hoarding profits for quite a while, waiting for demand to pick back up. That's why most of the tax cuts we've passed during the recession haven't been too effective, and a lot less effective than spending on infrastructure and aid to the poor. The former builds long-term economic growth, and the latter gets immediately injected back into the economy.

If you made it all the way through, I'm impressed. I'd also like to hear what you think. Anything I should've included? What's your path to an eventual balanced budget? Comment away...

Update: Added several links and charts for clarity and further information, and made a few layout corrections.